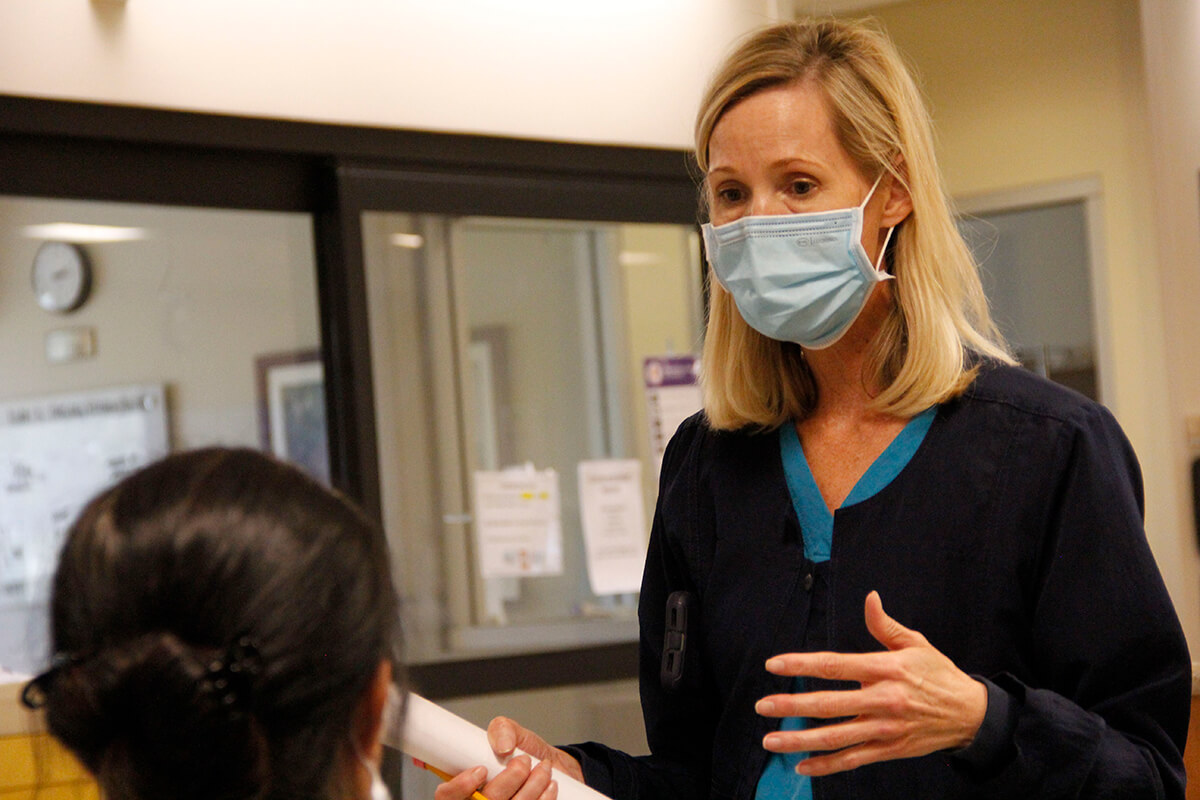

‘Things have changed so rapidly’: Infection preventionist navigates ever-changing guidelines to keep frontlines safe amid pandemic

In a year when the world has been focused on how to stop the spread of a novel viral infection, it has made Amy Lenz’s job all the more critical.

As an infection prevention coordinator, Amy bears responsibility for discerning the ever-changing guidelines handed down by local, state and federal public health agencies and putting practices into place to keep patients and her co-workers on the frontlines safe from a virus about which we know little.

“Things last year changed so rapidly,” Amy said. “We were putting processes into place for things that never existed. We had no previous experience to rely upon, and you’re learning as you go.”

Infection preventionists are trained to make decisions based upon science and data, establishing best practices in hospitals that rely on prior research and studies. For COVID-19, none of that existed.

The looming prospect of having a hospital filled with infectious COVID-19 patients led to a series of questions that had never been asked before.

How do we run a PICC line on a COVID-19 patient when those procedures used to be done in a separate department of the hospital?

How do we run a code quickly for a COVID-19 patient with isolation precautions requiring copious amounts of personal protective equipment?

How do we limit the amount of time frontline staff spend in COVID-19 rooms?

How do we deliver negative pressure to rooms for COVID-19 patients if we fill up the existing isolation rooms we have?

Every question required an infection preventionist to weigh-in and determine best practices to limit exposure and keep patients and caregivers safe.

“I’ve learned more in one year than I have in my previous seven,” Amy said. “It was inspiring to work with a team to create processes that had never been done before.”

In the hospital, Amy has a set of eagle eyes.

Chairs with upholstery tears in the lobby; cardboard boxes sitting in a patient care area; a ceiling tile with a water stain — all of those are possible vectors for infection that most would overlook, unless you’re a state surveyor or infection preventionist.

On a routine basis, Amy walks the hospital with a group of leaders for safety rounds, performing a deep dive of these types of issues. They move from room-to-room, unit-to-unit meticulously inspecting areas to ensure medical equipment is being stored properly; that fire doors are functioning; that refrigeration units are running at proper temperatures; and that proper infection prevention protocols are being followed, among a menagerie of other things.

They create a list of findings and then go to work improving the process. Often, it’s Amy who educates nurses and other frontline staff on the best practices.

“We get a lot of work done when we’re in the office, and we feel productive,” Amy said. “But it’s when I'm rounding in the hospital, being with patients and answering nurses questions that I really feel fulfilled. It’s the happiest I can be.”

During the pandemic, those rounds have become a critical moment when frontline staff who have been confused and scared about the ever-changing flood of recommendations and guidelines around Coronavirus could get straight-talk from somebody they trust.

On that particular day, Amy was rounding to educate nursing leaders about new guidelines discontinuing isolation precautions for COVID-19 patients.

Those are the precautions that state COVID-19 patients should be in negative pressure rooms with HEPA filters running, and that caregivers are required to wear gowns, face shields, N95 respirator masks and gloves to protect themselves. If a procedures is being performed that could lead to aerosolization — most often caused by a patient coughing — caregivers are required to wear Portable Air Powered Respirators (PAPRs), which look like spacesuits with a motor attached to the back that recirculates clean air for the caregiver.

The CDC released guidance this month that patients who are 20 days past onset of severe illness or a positive test result don’t need to be isolated because their research shows the virus can’t replicate after that point. In the cases of patients with milder COVID-19 symptoms, the virus hasn’t replicated past 10 days of onset, according to the CDC.

Frontline caregivers were understandably confused and, in some cases, upset about the relaxing of safeguards. It’s a massive shift in the way care is delivered for COVID-19 patients that runs counter to the processes that have been established throughout the year. Isolation precautions are the thin veil of safety long relied upon to reduce exposure and stay safe.

“This has been the biggest challenge of the pandemic,” Amy said. “This virus is so new, and there have been so many changes in guidelines from the CDC that our staff don’t know what to trust.”

As Amy walks the halls during rounds, she’s stopped over and over by nurses who have questions about the guidelines, about how much PPE they are allowed to wear and whether it’s really safe.

It’s a balancing act for Amy, who all year has been watching guidelines shift and change as researchers learn more about the virus daily. In this case, she and the chief medical officer are proceeding with caution. Despite CDC guidelines, if a care team determines a patient should continue on isolation precautions past 20 days, they won’t insist they be taken off.

“Don’t stop your nurses from wearing all their PPE if that’s what they want,” Amy tells a nurse leader. “Let them be comfortable and feel safe.”